My son got in the car this week and told me he was getting a B in one of his classes.

“The teacher hates me for no reason,” he defended.

I had the “If you don’t put forth your best effort now, you’ll never get into college or get a job and you’ll spend the rest of your life living in our basement” lecture all ready to go, when he quickly followed with…

“Actually there is a reason. I’m really annoying in that class.”

I don’t think he said it to spare himself the lecture, but it had that effect. In a moment I went from annoyed to proud.

There are many false beliefs we hold because they fit a narrative.

“I’m awesome so my bad outcomes can’t be my fault” is one of those narratives. It’s called self-serving bias*—the tendency to protect our ego by taking credit for our successes and blaming others for our failures. It’s appealing, but it’s often false. Just like it was with my son.

This is why I spared my son the lecture when he confessed that his behavior likely played a role in his grade. I still wasn’t happy about the B, but I was impressed that he was able to push aside his ego to recognize that it wasn’t simply bias.

Not every story we tell ourselves is true.

That applies to teenage boys…just as much as it applies to grown women.

Over the years I’ve shifted more and more of my efforts—speaking, writing, advising—to serving women. Many influential people in my life have advised against this, telling me that it would be more lucrative to speak to the entire population, rather than half of it. I’ve ignored that advice because I believe—based on lots of data—that women face obstacles that men don’t. I also feel called to help women because I’m in a privileged position to do so—49 years of lived experience as a woman combined with 25 years of expertise in behavioral science.

Because I’m knee-deep in women’s disadvantage every day, I’ve found myself shocked when some of the narratives I’ve held about our misfortune turn out not to be true.

This was the case last week, when Adam Grant** sent me an article challenging a common belief about women. Notably, this isn’t the first time I’ve been surprised. Two other false beliefs, in particular, stand out to me.

Not only are these false beliefs…well, false (which is reason enough to dump them), they’re also harmful to women in different ways.

So I’m here to set the record straight based on the data.

1. Women are on a “glass cliff”

It’s very clear that we love creating two-word, height-related metaphors to describe women’s challenges: Such as the “broken rung,” the “leaky middle,” the “glass ceiling,” and the “glass cliff”—the narrative that women are set up to fail by being more likely to be tapped for leadership in times of crisis.

Turns out, according to the article that Adam sent me last week, the evidence suggests the opposite:

The more stable a company’s financial situation, the greater the likelihood a woman will be appointed to CEO.

This is not to say that all the news is good: Women are still way less likely on average to rise to the C-suite than their male peers. But it is very good news to see data that senior women aren’t disproportionately set up to fail.

The article mentions a few reasons that setting the record straight is important, all valid. Of these, the most noteworthy one in my mind is that this false narrative may discourage talented women from seeking or accepting leadership positions if they assume that any position they are offered must be a damaged one.

As both a women’s advocate and a person who dislikes unnecessary terminology, I’m happy to report that the “glass cliff” seems like one metaphor we can ditch for now.

2. Women are underpaid

Before you get too excited, this statement is still true—on average.

But it’s not true for all women.

I was struck when I first read this article in HBR, titled “Most People Have No Idea Whether They Are Paid Fairly”.

The point of the article is that companies benefit when they are more transparent about pay because we see pay is as a signal of how much we are respected and valued (i.e., our status!!). If we don’t feel paid appropriately, we don’t feel respected—then we’re unhappy and often leave.

I fully agree.

However, that’s not what I found most interesting about the article. What hit me was the data (from a survey of 71,000 people) on how individuals perceive their own pay.

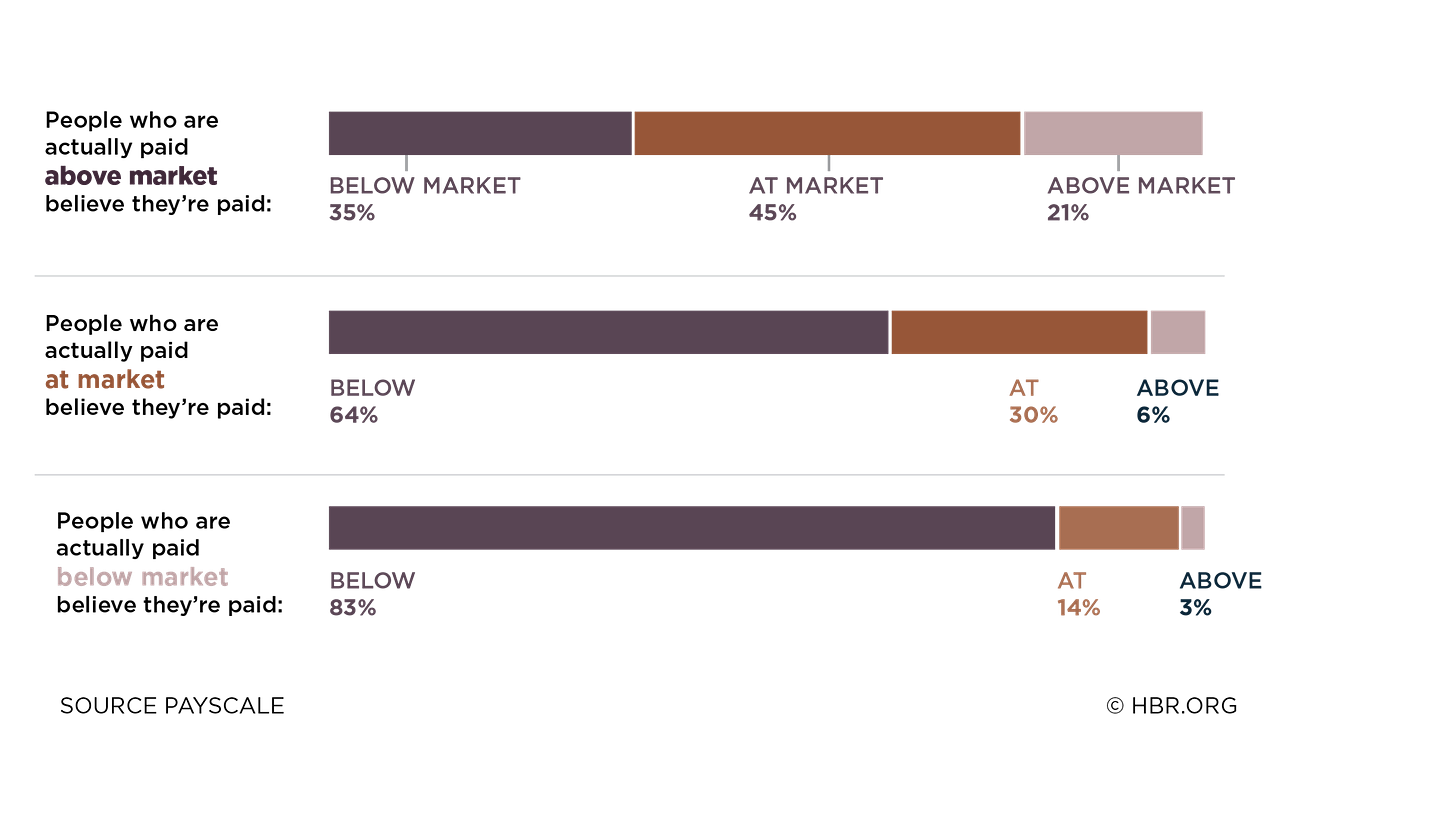

If you’ve ever seen me talk about negotiation on stage, chances are I’ve shown you this chart from the article.

Several things stood out to me from this graph (and the additional supporting data presented in the text of the article):

Pay perceptions often don’t match reality, with more people thinking they are underpaid than actually are. Another example of a self-serving story we tell ourselves.

Two-thirds of people paid at market rates thought they were underpaid!!

Only 20% of people who are paid above market recognize it.

And…wait for it…

Women who were OVERPAID (e.g., paid above market) were 18% more likely to believe they are UNDERPAID than overpaid men.

That blew my mind when I first read it. But it makes total sense.

Because women are underpaid on average it’s an easy leap to believe that all women are always underpaid. But that’s not true.

So let me say it loud for the people in the back:

The fact that women are generally underpaid does not automatically mean that YOU are underpaid.

There are women who are paid more than market. Maybe you’re not one of them. But maybe you are. Do you know for sure?

To be clear, I am 1000% in support of ALL women being paid more—even to the point of being above market. We have above-average talent so why not get above-average pay for it? I’m all in.

But believing you’re underpaid when you’re actually not is detrimental for at least three reasons:

It makes you unhappy: Again pay is one way we judge our status, and feeling disrespected is miserable. Don’t suffer unnecessarily.

It could lower your status: If you think you are underpaid, it would be natural to complain about it to everyone who would listen. But if you heard a person you knew was overpaid always whining about how underpaid they were, what would you think of them? The would probably come across as out-of-touch, illogical, selfish, greedy, etc. (aka, not likeable badass). Complaining about a pay gap that doesn’t exist is a surefire way to lose respect from your audience.

It sets you up to fail in your negotiations: There is no reason that you can’t be overpaid AND still negotiate for even more money. I’m sure there’s a mediocre man in your world doing this successfully right now, so why not you? BUT, asking for more money when you are overpaid requires a different rationale and data than asking for more money when you are underpaid. If you tell your boss you’re underpaid when she knows that’s not true, you’ll look unprepared and lose credibility. Being realistic about your current pay helps you develop a better negotiation strategy—one focused on the tremendous value you deliver.

I also think that when you advise other women on pay negotiations—something I do often and you might, too—don’t take it as a given that they are underpaid just because they say so. The first question I ask anyone who comes to me for pay negotiation advice is, “How does your current pay compare to others who do similar work, either inside or outside your organization, and what’s your evidence?” If they can’t answer me, I send them off and tell them to come back to me when they have the data (and have read the HBR article).

3. Women don’t ask

Speaking of pay, you’ve likely heard the claim that one reason women are underpaid is that they are less likely to initiate negotiations about pay (or anything else) than men.

Based on the initial data from 20-ish years ago, I have no doubt this was once true.

When Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever published their book Women Don’t Ask, those of us who taught negotiation courses were ecstatic. Finally an evidence-based explanation for women’s worse negotiation outcomes that we could do something about.

So we—negotiation educators—got to work. The “women don’t ask” data ended up in virtually every negotiation course, including mine, and countless articles were written about the topic. I’d be shocked if there is any woman reading this who hasn’t been exposed to that finding one or more times in her life. We got the word out.

And guess what? It worked! Kind of…

Research published in 2024 revealed that women are now negotiating—at least for pay—as often or more than men. But, despite equal or greater rates of negotiating, women are still not getting as much in these pay negotiations as men.

For an easy-to-digest summary of the research and why it matters, you can check out this article or watch this short video.

Overall, I see this as good news.

We spent twenty years telling women to negotiate more, and now they do!

One problem fixed.

Is there still more that needs to be done? Absolutely.

We need to get women’s negotiated outcomes on par with men’s—both by giving women effective strategies to negotiate effectively in the face of bias, AND squashing that bias once and for all.

We will get there. I know it.

But to get there, we need to revise our narrative about why women aren’t succeeding in negotiations. As the researchers point out, believing that “women don’t ask” hurts women because it implies that our poor negotiation outcomes are our fault—if we only had the courage to ask, all of our problems would be solved. This perpetuates inaccurate negative views of women as less skilled negotiators, and also reduces support for legislative and policy efforts aimed at improving women’s pay.

So to set the record straight, the current data suggests that the tagline needs revision: “Women do ask, they just don’t get.”

My latest:

I’m experimenting with adding this section as the standard end to my newsletters—a place to let you know what is going on in my life since I last wrote.

I am fully stealing this from Amy Gallo, who, among other things, is the host of HBR’s Women at Work podcast. She’s also an author, off-the-charts likeable badass, women’s advocate, and conflict expert. If you are not already following her and subscribing to her newsletter, please correct that asap. You can thank me later.

I love Amy’s newsletter, and especially this section. So I hope she will agree that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. And it will also be a great test of whether she reads my entire newsletter :-).

Here’s what’s keeping me busy at the moment:

Speaking: Talking to groups, both in-person or virtual, is still where I spend the bulk of my time these days. I get to go to cool places, meet amazing new people, and spread the messages of Likeable Badass. If you or anyone else ever wants to inquire about bringing me to your event, best way to do it is to fill out this form on my website and someone on my team will reach out.

Likeable Badass workbook: If you’ve ever searched for my book on Amazon, you might have noticed that the other items that come up are workbooks related to the book—except they aren’t written by me! Turns out there’s nothing illegal about this so I can’t stop the imitators (which actually doesn’t feel that flattering, so maybe apologies to Amy are in order). But it has been very embarrassing when people have proudly showed me the workbook they bought and I have no idea what they are getting.

At the same time, I’ve received countless direct requests to create a workbook. So I am!

It will be available soon to all newsletter subscribers and it will be free to download. Stay tuned for an announcement when it’s ready.

If you know someone who wants the workbook, share this post and tell them to subscribe.

Events for individuals: Historically, the only way for an individual to work with me was to work for an organization who hired me to speak. I wrote Likeable Badass to make the science and strategies I share in those talks accessible to more people. In that vein, I am now creating two programs for individuals—one virtual and one in-person. These are full-day workshops designed to help individuals apply the tools in the book. Planning is in early stages, but I am hoping for a virtual program in the spring and an in-person program in Chicago in the fall. More to come as details are solidified! And, if there are things you would really like to see in these programs, let me know!!

The rest of my day:

As soon as I hit “publish” I’ll hop on the Peloton bike for a 60-min ride (TBD). One of my “resolution-ish” goals for the year is to do an hour of cardio on both Saturday and Sunday (and shorter efforts during the busy week).

Then I’ll finish putting my holiday decorations away. I got them as far as the basement, but now they need to be boxed for storage. I’ve been procrastinating because I hate this step—and because I was too busy this month not doing Dry January.

After that, watching NFL playoffs with my family. Go Bills! I have no ties to Buffalo whatsoever, I just think they deserve a win.

Whatever your Sunday involves, I hope it makes you happy.

Cheers to success, friends!

*FWIW I’ve always found that if a psychological finding has its own Wikipedia page, it’s a good indicator that it’s a widespread phenomenon. As Michael Scott from The Office once said: “Wikipedia is the best thing ever. Anyone in the world can write anything they want, so you know you are getting the best possible information.”

**Adam sending me the article is not relevant to the story but I mention it because a) I thought he should get credit for making me aware of this new research and b) I know a lot of my readers are big AG fans and seem to get a kick out if it every time I mention him.

Super interesting. I spent a long time in higher ad and that “market pay” seems impossible to figure out.

I cannot wait for the workbook and the in person event in Chicago and probably the virtual event . Recommended LB to a new friend (random stranger) today in Chicago.

As always, such useful (and fun to read) content! I love that we've moved the needle by getting women to ask and hopeful that in next few years (please, let it not be 20), we can also help women get the pay they deserve. My Christmas village is still out, but I am doing dry January, so waiting for next week to put all the houses, cords, and tiny light bulbs back in their boxes.